Dawn of the Dead Design

We’ve already written about the fact that the open office concept is dead. This article from Inc. — “It’s Official: Open Plan Offices Are Now the Dumbest Management Fad of All Time” — is just another stake through its heart. But some things die harder than others. That’s why we have Dracula and zombies. It’s why Freddie Kruger, Jason Voorhees, and their respective movie franchises can never be put to rest. And it’s why we seem determined to perpetuate force-fed collaboration unto self-defeat.

Case in point: “You Could Be Too Much of a Team Player“, published in The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), says this, in part:

The splintering of demands that marks a collaborative workplace … can also hurt your organization … Many white-collar employees who in the past would have worked side-by-side with a few colleagues now spend 85% of their time collaborating with multiple teams of co-workers … The volume and diversity of collaborative demands on employees have risen 50% in the past decade.

As the WSJ article makes clear, the open office design isn’t the only culprit when it comes to defeating teams and teamwork and to depriving people of privacy and the ability to concentrate. And while setting personal boundaries when it comes to things like meetings, conference calls, email traffic, instant messaging, and other impromptu interruptions is essential, design can be the key to restoring comfort, productivity, and sanity to the workplace.

Purposeful Control

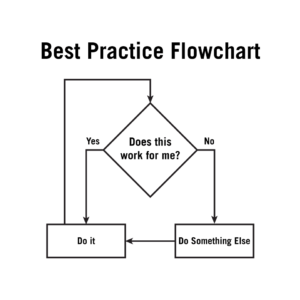

Some aspects of stress and distraction can’t be controlled. Some stresses and distractions come with particular kinds of jobs. Some of them are matters of individual temperament. But others can be managed by designing particular elements into the workspace. Those elements can include but will definitely not be limited to:

- Inviting, comfortable meeting rooms.

- Quiet, comfortable private offices.

- Engaging, comfortable shared spaces for breaks, collaborative work, and other users.

It’s hard to imagine much could go wrong if we design workspaces for the people who have to spend a third of their lives in them.

Practicality by Design

We’re not quite convinced it’s possible to be too much of a team player. But this excerpt from the book, Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days by Jake Knapp, suggests we might have been a bit too hasty in adopting open offices and a bit too forgetful in the bargain:

At Yale in 1958 individuals competed with brainstorming groups to solve the same problem. The individuals dominated. They generated more solutions, and their solutions were independently judged to be higher quality and more original … And yet … over a half century later, teams are still running group brainstorms.

Maybe the best thing we can do is to think of the people who work in the spaces we design as being more intelligent than zombies, more creative than interchangeable automatons. If we do, we’ll give them the space they need to work in teams and the privacy they need to work alone. And those people will likely be more satisfied and more productive.

At the very least, they won’t feel like they’re in a bad horror movie, even if it is a classic.